Addressing The Problem with Homework

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

Who wouldn’t like the idea of student-centered learning? The very name captures everything that education is supposed to be: an experience designed around students. While few would argue against student-centered learning, educators still have a long way to go in designing a system that matches student needs and interests.

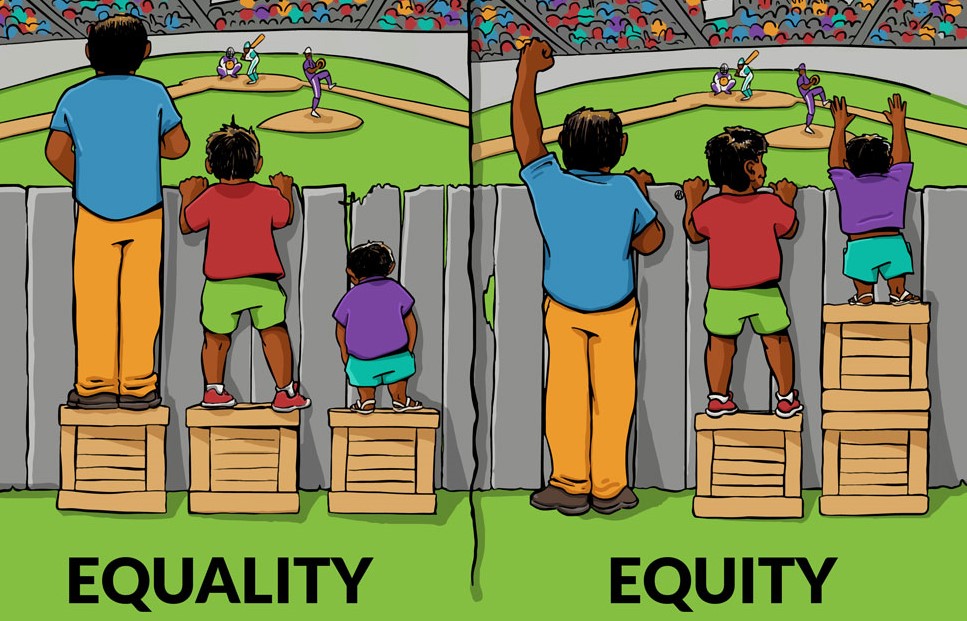

A common objection to designing student-centered classrooms is the dreaded, “It won’t work with these students.” This refrain is often used to justify stringent discipline and teacher-centered instruction, especially for low-income students and students of color. Proponents believe that struggling students need to focus on “the basics” or to develop “grit.” Poor students, the thinking goes, do not have the luxury of exploring collaboration and inquiry. Equity in education, however, demands that all students experience empowering and impactful classrooms.

The concepts of grit and discipline have been hot topics in education, strongly advocated by some charter schools. These schools celebrate their no-nonsense discipline, even if it means suspending six year-old children. In other settings, students are taught that grit is the secret ingredient to success. The unspoken sub-text, of course, is that low income children and families simply haven’t tried enough.

In reality, many low-income students come to school with a unique host of challenges. These include hunger, academic gaps, learning differences, and social-emotional needs. That does not mean they deserve a less rigorous and student-centered education. In order to provide an equitable experience in our schools, we must better understand the unique needs of economically disadvantaged students. Students who have negative associations with authority may require additional support to take ownership of their learning. Those who don’t feel safe and supported may need help to work collaboratively with their peers.

I recently worked with a pair of teachers who care deeply about their students. They work long days to plan lessons that involve creativity and discussion. They make and remake assessments to better understand the needs of their students. While debriefing one of their lessons, I suggested we plan a more student-centered lesson for my next visit. As soon as I saw the looks on their faces, I regretted my choice of words. One asked, “You don’t think our class is student-centered?”

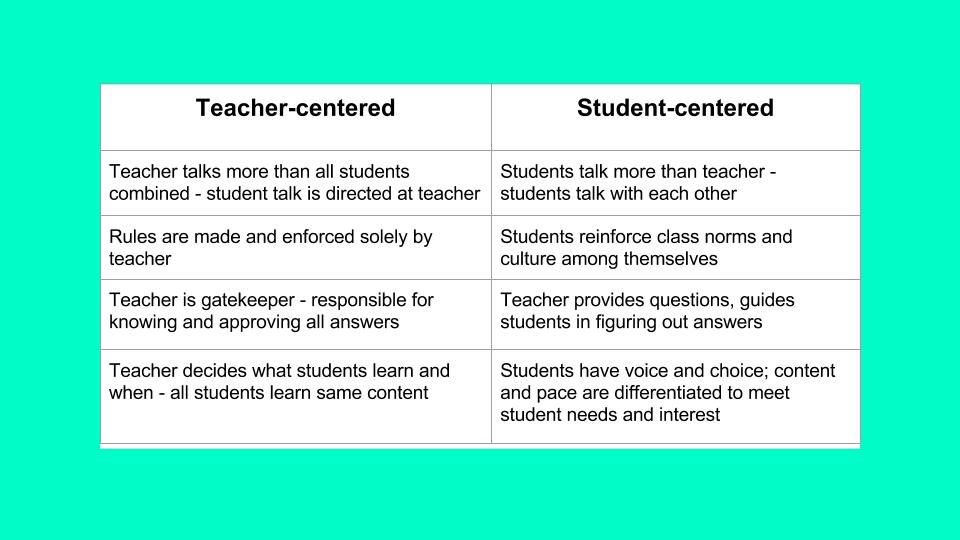

From where I was sitting, the lesson had all the signs of teacher-centered learning. The teachers talked throughout the entire lesson. The desks were in rows facing the front of the room. Students received packets that specified and assessed everything they would learn that day.

So why the confusion? I immediately realized that these teachers understood student-centered to mean “caring about their students,” which these teachers truly do. Real student-centered learning, though, is about more than good intentions: it is about rethinking the classroom experience in a way that empowers and engages students.

The table above lists some indicators of student-centered vs. teacher-centered classrooms. It is by no means exhaustive. The main distinction is that in student-centered classrooms, students are given the trust and respect to make important decisions about their own learning.

In a traditional classroom, the teacher’s role is to be the ultimate source of knowledge and wisdom. This unfair expectation causes undue stress for both teachers and students. It forces both to act in ways that limit their potential. Students learn that their opinions are unimportant, and that their job is to sit and listen. A great deal of research, however, has demonstrated that interactive learning leads to deeper comprehension and better retention.

Perhaps the strongest justification for student-centered learning, though, is common sense. Think about a time you were forced to learn something you didn’t care about.

What did it feel like? What was the outcome?

Compare that experience to a time you were passionate about what you were learning. Did you need someone to give you assignments and test your understanding?

While some of what students learn in a traditional classroom is crucial to their future success, much is not. Further, many skills required for success in work and life that are not taught in school. Inviting students to have a voice in what they learn and how they learn helps to make the learning more relevant. As a result, student engagement and motivation increase.

Even when educators are committed to providing equitable student-centered experiences for their students, it can be challenging to create a sense of ownership among students who are disengaged. While behavioral and social-emotional problems are often cited as reasons to avoid student-centered methods in low-income schools, these issues actually highlight the need to provide underprivileged students the opportunity to guide their own learning.

Students from privileged backgrounds often come to school with a belief in the benevolence of authority. The system was designed for them, and experience teaches them that if they do as they’re told, they will earn a life of comfort and success.

For less privileged students, the opposite is often true. Non-white and low-income students may have a harder time seeing school as a gateway to success. Students of color are often faced with authority figures whose background is different from their own. This can make it more difficult to identify with these authority figures. By middle school, many students of color have encountered enough systemic racism that they may reasonably question the benevolence of authority. Teacher-directed classrooms can reinforce their belief that they are not understood or that their opinions and goals do not matter.

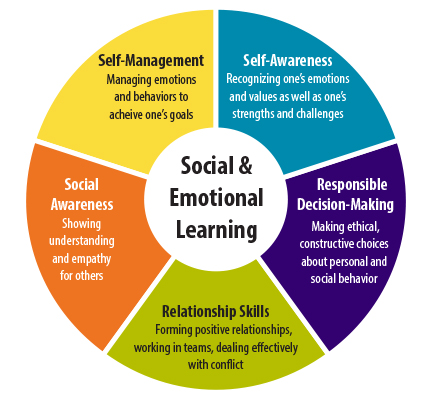

In addition to establishing trust in the system, student-centered environments also help students develop social-emotional skills. Concrete tasks like taking notes, memorizing, and passing tests rely almost exclusively on academic skills. Developing goals, researching, and collaborating with peers all require executive function, a crucial element of future success in life. In other words, when students internalize the structure normally imposed by teachers, they can take these skills with them beyond the end of the school year. By creating classroom cultures that value creativity, persistence, and collaboration, teachers can help prepare all types of students for success in school and in life.

For more information on how student-centered learning can help close the achievement gap, see this study from Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. For more about the integration of social-emotional learning into school programs, refer to the CASEL website.

No classroom is 100% student-centered or teacher-directed. Have you moved towards a more student-centered approach? How has it worked out for you? Tell us about your school or classroom in the comments below.

Remote coaching can provide the support and advice you need to bring student-centered learning to your classroom.

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

Does the Danielson Rubric improve teaching? Maybe it’s an unfair question. After all, it’s a rubric, not a training program. But…

Teaching word problems takes more than key words. The Polya Process helps your students think strategically and make sense of story problems.