Addressing The Problem with Homework

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

Most educators know that small group instruction works. And if they don’t, there’s ample evidence to prove it.

But walk down the hall of most K-12 schools, and you can expect to see most teachers standing at the front of the room. There may be an occasional cold call. But for the most part, teachers talk, and students listen.

Part of the reason teachers disagree is because small group instruction means different things to different people.

In some schools, teachers are required to arrange their desks in groups, in the hopes of promoting collaboration. Other schools focus on “learning stations” or “centers” where students move in groups from activity to activity. But it’s a lot easier to change seating arrangements than it is to change how we teach.

Many of us went to school in a time when whole-group learning was the standard. So it can be hard to tell which model of small group instruction is best. And once we pick a model, how do we do it right? And how can we tell whether it’s working?

An elementary school principal once asked me to help her increase student engagement through small group instruction.

“Sister Dorothy” had recently attended a conference where she learned about the station-rotation model. She was enthralled by the idea. Students would have a technology table, where they engaged in personalized learning.

At another station, they would complete paper-based collaborative activities. And at a third station, teachers would work with a small group of students.

She wanted teachers to use cooking timers, and when the bell dinged, the students would quickly and quietly move from one station to the next.

“As I walk down the hall,” she explained, “I want to see room after room of station rotations, humming like clockwork.”

But there was a catch. These teachers had never done small group instruction. Few had ever used technology in their classrooms. They weren’t familiar with effective group work strategies or how to teach students to collaborate.

I suggested we work on each learning model in sequence. We could start by having all students explore personalized learning. Or we could start with collaborative learning. Or we could show the teachers how to use data to plan small group lessons for leveled groups.

But Sister Dorothy wasn’t interested in any of that. “I want three stations, timers, and students moving from group to group every ten minutes.”

We set it up. She walked down the hallway a few times to verify it was “working.” And a week later, everyone went back to what they’d always done – lecturing from the front.

This example reflects why many teachers struggle with small group instruction. When a teacher stands in front of a room filled with desks in rows, it’s easy to see that it’s a teacher-centered lesson.

Many educators know that we should allow students to work in groups. And it’s a lot easier to change seating arrangements than it is to change our instructional methods.

So we get learning centers with multiple choice worksheets. Or a kidney-shaped table with a teacher delivering the same old lecture to five students at a time.

But what matters is harder to measure. Are students engaging in active, inquiry-based learning? Are they learning to collaborate effectively?

Small group instruction is meant to increase student engagement. But actual engagement can be difficult to define, and even more difficult to measure.

There are a dozen or more models of small group instruction being used in schools today. Project-based learning can provide wonderful opportunities for students to engage in thoughtful learning, while working with their peers. The jigsaw model sounds interesting as well, though I haven’t seen it used effectively in a real classroom. Both of these are somewhat complex, and could be overwhelming for educators who are new to small group instruction.

In my experience, the workshop model is the most effective and easiest to implement. I also think stations are worth addressing, as they are extremely popular. They also have a lot of potential, but can easily go off-track.

Stations are a popular but challenging model for small-group instruction.

I hear from a lot of teachers who are required to use stations in their classes. Many are overwhelmed. Frequently, these are elementary teachers, who are responsible for teaching their students language arts, math, social studies, and maybe even science. Now, instead of planning one lesson per subject, they need to plan five stations.

It’s easy to see why many administrators love stations. It keeps the teacher from lecturing for an entire period. There’s also a common myth about attention spans, which claims that a child’s attention span can be found by doubling their age. If you believe that seven-year-olds can only focus for 14 minutes, of course it makes sense to have them move from station to station every ten minutes.

The reality is that attention has more to do with the quality of an activity that its length. Deliver a monotone lecture, and students are tuned out in under a minute. Design an engaging activity, and students can easily focus for an entire period.

Here are three tips to making stations effective without spending hours planning for each lesson.

Before you try to use stations for an actual learning activity, make sure students understand how they need to move. Students will be more engaged and energized by moving about the room. But if you’re not careful, stations can easily devolve into chaos.

Students need to understand that when the timer goes off, they need to move to the next station. Even if they’re not finished.

Give them a warning so they have time to wrap-up what they’re doing. Anyone gets frustrated when they’re interrupted in the middle of a task, and students are no different.

When it’s time to switch, make sure everyone stops what they’re doing. All it takes is one student to lag behind to throw off the entire rotation.

The key to good centers is coming up with a simple, yet engaging activity. Of course, students should also learn something valuable.

I see a lot of “stations” or “centers” activities sold online that are just worksheets. Simply having students move around the room to do worksheets doesn’t count as small group instruction.

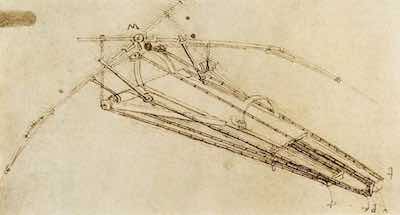

One of my colleagues designed a great stations activity to introduce a unit on the Renaissance. It was nothing more than a set of ten folders, each of which had an image with a question. One was a Leonardo Da Vinci flying machine sketch, with the question “What do you think this machine does?” Another was Don Quixote charging at a windmill with the question, “What is the man on the horse doing?”

Students had an absolute blast. They had never seen these images, so their curiosity was sparked. And the open-ended questions got them thinking creatively about the Renaissance.

It did a great job of generating interest in the upcoming unit, and giving students context for what they were about to learn.

You can find a number of engaging classroom activities for any subject in our resources shop.

I once designed a stations activity on area of for grad school. One station had a square cut out of graph paper. Students were to find the area by counting the squares. Next, they found the area of a triangle by folding a square in half. At another station, they used the area formula.

I even set up a google docs for them to record their answers. At the end, we would go over the group’s responses.

I used it once. I realized too late, that the stations needed to be done in a specific order – but there was no way to do that without having groups wait around. And students weren’t connecting the dots as I’d hoped.

I figured I’d eventually work out the kinks, but I never did. What teacher has the time to design such complex activities on a regular basis?

The beauty of the Renaissance stations was their simplicity. I ended up borrowing the model for the rest of the units in the course. All I did was find ten images for our China unit, and wrote ten question. Then I found ten for our Medieval Europe unit, and so on.

I even used the model as a demo lesson for an interview. They were learning about Andrew Jackson, so I found ten political cartoons about Old Hickory.

Students got a lot more value from the simple activities. Notice, I didn’t say easy. The questions were open-ended, and prompted some really deep thinking from students. But the directions, structure, and my preparation time were all pretty simple.

I could find ten images and write ten questions in around 30 minutes. Given the benefit students gained from the activity, that was definitely time well-spent.

While stations can be a simple way to engage students and spark inquiry, they don’t allow students to engage deeply with a topic. They also aren’t great for promoting mastery of standards.

Stations make great appetizers. But when I want small group instruction to promote deep inquiry, my go-to model is the workshop.

The workshop lesson model was first developed by John Van de Walle for use in math classes. But his three-part model has been adapted for use in any subject.

Workshop lessons can be extremely engaging and effective. But they are very different from what most students and teachers are used to. Here are four keys to an effective workshop.

There’s more than one right way to group students. But there are hundreds of wrong ways.

The most ineffective way to group students is randomly. If you want students to pick their groups, that’s a choice. And if you trust them to pick their teams, this could be the right approach. Or maybe you want them to choose the wrong partners so they learn how to pick better.

There is also a time and place for leveled groups. But you should only use leveled groups if you have different activities for each group. If you level students and give them the same activity, all your doing is magnifying inequities.

I usually start by ensuring each group has a strong leader who will help the group focus. Then, I split up students who tend to tray off-task. I also look for complementary skills, like grouping a good writer with a good public speaker.

Inquiry-based learning is supposed to be challenging. When students engage in productive struggle, they learn more, develop confidence, and retain what they’ve learned.

We often underestimate our students. When students are disengaged, they don’t learn much. Many teachers misinterpret their achievement as their potential. When we slow down and overscaffold, students can become even more disengaged. It becomes a vicious cycle.

It’s a delicate balance. We need to make sure we are targeting a student’s Zone of Proximal Development. A good inquiry-based activity should push students just outside their comfort zone.

If students breeze through the activity, we haven’t created productive struggle. And if they don’t know where to begin, we need to lower the bar.

If students are new to workshop, we may want to use simpler content while keeping the rigor of the assignment. They will be learning how to learn through inquiry, so we should let them focus on one thing at a time.

When I plan a workshop lesson with a teacher who is new to inquiry learning, many of them can’t help but spoil the surprise.

We find a standard, and together we plan a great workshop. It has an engaging hook, a rigorous activity, and a meaningful close. Sometimes I even do a demo lesson beforehand.

Then, at the last minute, the teacher gets cold feet. Instead of going through with the inquiry-based approach, many will explain step-by-step, how students should solve the problem.

In math classes, this often means giving students a formula. In the humanities, it means telling students what points to address in a short answer question.

Once the students start working, they quickly repeat what the teacher told them. They finish early. And they learn, once again, that all the right answers come from the teacher.

When introducing a workshop, the goal, as Dan Meyers puts it, is to “bait the hook.” Show students why they should care about the topic. Show them how it connects to what they already know.

But just don’t show them how to answer the question.

Workshop lessons are all about creating a lively and creative atmosphere. But that doesn’t mean there is no structure.

In order for students to learn through exploration, they need boundaries.

When I pass out an activity and just tell students to get started, they tend to take a while to get going. They’ll talk about the game last night. They’ll spend 20 minutes deciding who does what job.

It’s amazing how much more productive students are when I give them a time limit. As soon as they see a timer counting down, they get down to business.

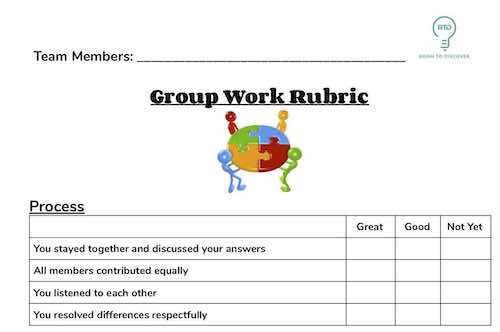

A group work rubric is helpful for two reasons. It helps students understand what’s expected. And it lets them know they are receiving a grade for the activity.

I know some educators believe students shouldn’t be graded on classwork. And I agree, in theory. I’m in favor of doing away with grades completely. But if we grade tests and not classwork we are sending them a confusing message. “Today doesn’t matter. Next Friday does.”

And then we wonder why students don’t put their best effort in on regular class days. Or why they all start looking for help the day before a test.

Unless you’re prepared to stop grading your students, let them know that workshop matters. Assign a grade.

If you’ve been wanting to try small group instruction, I hope this article has given you enough to get started. If you still have any burning questions, post them in our Facebook group, the Reflective Teachers Community.

Stations are relatively easier to implement. All you need to do is put activities on separate tables, and have students move from one to the next.

Workshops require a bit more of a shift. It’s very different from a lecture-based or textbook-based approach to teaching. If you’d like to start with a pre-made lesson, you can find some on our Teachers Pay Teachers page:

You can also download our free workshop lesson plan template. It walks you through the key elements of planning a three-part workshop, with suggestions for each part of your lesson.

Author Bio

Jeff Lisciandrello is the founder of Room to Discover and an education consultant specializing in student-centered learning. His 3-Bridges Design for Learning helps schools explore innovative practices within traditional settings. He enjoys helping educators embrace inquiry-based and personalized approaches to instruction. You can connect with him via Twitter @EdTechJeff

Jeff Lisciandrello is the founder of Room to Discover and an education consultant specializing in student-centered learning. His 3-Bridges Design for Learning helps schools explore innovative practices within traditional settings. He enjoys helping educators embrace inquiry-based and personalized approaches to instruction. You can connect with him via Twitter @EdTechJeff

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

Does the Danielson Rubric improve teaching? Maybe it’s an unfair question. After all, it’s a rubric, not a training program. But…

Teaching word problems takes more than key words. The Polya Process helps your students think strategically and make sense of story problems.