Addressing The Problem with Homework

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

Should teachers be required to write learning objectives on the board? On the one hand, it seems like a sensible expectation. When a class period begins, shouldn’t students have a sense of what we hope to accomplish that day?

Understanding the why behind the what helps students feel invested in their learning. Investment increases student engagement, and it can make lessons more effective.

But too often, a so-called learning objective is just a reworded standard. And there is a big difference between a standard and a learning objective.

Standards are milestones. They set reasonable expectations for what students can achieve at each grade level. And standards help schools evaluate the effectiveness of their programs.

To some extent, standards should inform instruction. But it’s not as simple as “teaching standards.” Many education experts caution against teaching to the test, and for good reason.

When our teaching focuses on test prep, students suffer. They lose out on the richness of science, math, and the humanities. Classes become boring and stressful. And this type of learning doesn’t prepare students for the world outside the classroom.

As educators, our role is to create a bridge between students and standards. Since every school and every student is unique, each bridge should be unique as well.

But how can educators go beyond teaching the test? How can we ensure we are addressing standards without turning them into learning objectives?

Baseball provides a handy metaphor for the difference between standards and learning objectives.

Each aspect of the game (throwing, catching, hitting) represents a domain, or collection of standards.

Within the “hitting” domain would be a group of standards that break down a successful swing. Player keeps her eye on the ball. She grips the bat firmly and accurately. She bends her knees and steps into her swing.

A player who masters these elements of a good swing has a better chance of hitting the ball. And coaches should look for them to help their players improve.

But the problem comes when we turn these standards of success into learning objectives. Here’s an example of what that might look like.

On day one, we would focus on gripping the bat. The coach would talk about wooden bats vs. metal bats. He’d demonstrate a standard grip and how to choke up. He might call on a few players to answer questions about proper gripping technique.

Everyone would be sent off to work on their grip independently. At the start of the next practice, the coach would walk around and “check the homework,” verifying that each player had mastered the proper grip.

Many of you are already rolling your eyes at this approach. Of course, many of our players would already know how to hold a bat. For those players, the whole process is a waste of time. Others might benefit from a quick explanation and nothing more.

Some of our players would lack the hand strength to hold the bat properly. We can explain all we want, but they’re just not ready to master that skill at this time. What they need is time to mature. In the mean time, they should probably focus on other aspects of their swing.

I doubt that any of us would consider coaching this way. It would be incredibly boring for our players. And we’d be right to question whether it would even work.

But this is exactly how many of us deal with standards and learning objectives.

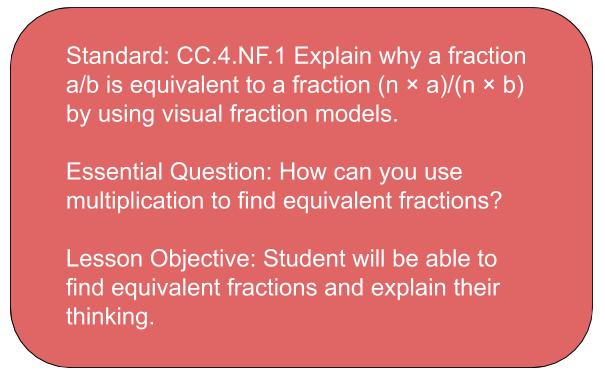

A few years ago, I was helping a 4th grade teacher redesign her fractions unit. She had just started fractions, but she already knew there was a problem.

She started each class by handing out an entrance ticket. But many students didn’t even try to complete it. The class was tuning out and fooling around during both mini-lessons and independent practice.

When she graded her exit tickets, there was almost no improvement from the entrance ticket.

I really felt for this teacher. She was following the lesson plan format mandated by the school, and taking her lesson objectives right out of the textbook.

Like many textbooks, they changed a few words in the standard and called it an essential question. Then they changed a few more and called it a lesson objective.

I looked over her pacing guide in disbelief. It called for six days on equivalent fractions. Then five days on demonstrating equivalence by multiplying.

Next, she would spend twelve days on adding fractions with the same denominator, interspersed with seven days on equivalence for fractions greater than one.

Just looking at the overview practically put me to sleep – I could only imagine how bored and frustrated the students would be!

For students who understand the basic concept of fractions, the pacing was way too slow. And students who didn’t understand the basics of fractions would still be lost.

To make the learning meaningful, I knew we needed to scrap the textbook’s pacing guide.

As a class, we spent a few days reviewing the fundamentals of fractions. We drew visual models. We discussed the meanings of numerators and denominators. It turned out that most students knew the numerator went on top and the denominator on the bottom. But few understood the concept of parts of a whole.

Once we’d covered the basics, we were able to cover the fourth grade fraction domain in just a few lessons.

Here are three tips to help you make sure your learning objectives are more than just reworded standards. You’ll keep your students engaged, and you’ll cover grade level content much more efficiently.

There need not be a one-to-one correspondence between standards and learning objectives. In fact, in most cases, there shouldn’t be.

In the baseball example above, the standards are all important. But they don’t need to be learned in sequence. The best way to learn is by swinging the bat. Some players might have a good grip, but take their eye off the ball. Another might have opposite issues.

But both players will improve by practicing their swing. They could even work in pairs and give each other feedback.

The point is that separating proficiency into its component parts may be useful for assessment. But it’s not the best way to learn.

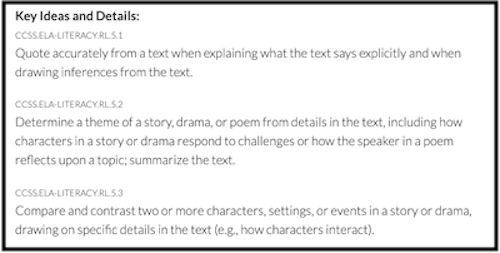

Consider the grade 5 literature standards for “Key Ideas and Details.” Students are expected to explain the literal meaning of a selection and make inferences. They’re expected to understand characters’ perspectives, summarize, and compare and contrast elements of a story.

These elements of reading comprehension overlap. So we don’t need to do each one on a different day.

Consider having the class complete a Story Analysis. This activity asks students to read a story and answer a range of standards-based questions about it.

Students could complete this same activity again and again, each time with a different story. And students with different learning profiles can each get what they need from the same activity.

Part of the problem with lesson objectives is that they are unrealistic. Whether we’re teaching long division or commas, students aren’t going to learn the concept all in one day.

Some students will come to the lesson already knowing how to divide or use a comma. Others are still learning to multiply or how to write a simple sentence.

To better meet the needs of diverse learners, we need to build flexibility into our planning. Focusing on unit plans, rather than lesson planning, makes that possible.

Extended planning allows learning to occur organically, when each child is ready. We can design activities that combine overlapping standards.

Say we combine ‘summarizing’ and ‘quote analysis.’ Some students may have a knack for summarizing a passage, and show proficiency on the first day. Others may be able to analyze individual quotes, but struggle to summarize the main idea of a passage.

If we complete similar activities throughout the unit, each student can master the skills in the order that fits how they learn.

But if we focus our objectives too narrowly, we’re forced to expect mastery at the end of a single lesson. We also become less efficient with our class time. Student A is breezing through day 1, with no productive struggle and little growth. Then, on day 2, she’s struggling to master a topic she needs more time for. Student B struggles on day 1, and learns little on day 2.

At the end of the day, we can’t pretend that students will learn on our schedule, simply because the pacing guide says so. We have to acknowledge that learning happens when students are ready to progress.

By focusing on units instead of lessons, we build slack into the system, while still ensuring we address standards.

Another benefit of planning by unit is the opportunity to incorporate inquiry-based learning. Research has repeatedly demonstrated the benefits of inquiry-based teaching. IBL is especially effective for deep learning and helping students develop collaborative skills.

Many teachers feel that inquiry-based lessons are too complicated. And it’s true that IBL can be challenging. Active lessons take longer to plan. And students need a growth mindset to have the confidence to learn through exploration. If they’re conditioned to learn through information delivery, it might take some mindset work for them to be successful.

Educators also worry about the class time required for inquiry-based learning. While it’s true that a lecture can convey information more quickly, that’s an unfair comparison. Students who learn through lecture retain less of what they learn. They also have difficulty applying their knowledge to solve problems.

When we take the long view, effective IBL can be a more efficient view of class time. When students learn deeply the first time, we can spend less time on repetition and review. IBL also makes it easier to connect multiple standards. So rather than covering each grade-level standard in sequence, a few meaningful inquiry lessons can support proficiency in an entire domain.

There are also benefits for student motivation. When my students engage in debate or student-led discussion, they happily analyze quotes to support their arguments. But if I give them a worksheet asking them to analyze a random collection of quotes, they groan.

If I teach them an algorithm for multiplying fractions, it’s just another thing to memorize. Instead, I’ll have them complete number sentence proofs, so they learn why the algorithm works. Not only is this more interesting, it combines standards across the NF (number as fraction) and OA (operations and algebraic reasoning) domains.

If you’ve been using standards as learning objectives, don’t worry. Just start by reconsidering your objective for one lesson or one unit.

If you use a textbook, the textbook may be guilty of setting the tone. Textbooks are notorious for simply turning standards into learning objectives.

To make your objectives meaningful, step back and reflect on the big picture. What do you want students to learn by the end of the year? Then, work backwards from the larger goal to build your individual units.

If you are in the middle of the year, start by unpacking your next unit. Think of the standards covered, and find or design a few activities that tie those standards together.

Build your unit around the activities rather than using the textbook pacing guide. Then, supplement with lessons from the textbook. Choose only the lessons that seem essential, or those in areas your students will need extra support. There’s no need to “cover” everything in the book.

If the idea of creating your own curriculum plans seems overwhelming, don’t go it alone. Resources like Achieve the Core and CoreStandards.org can help you better understand your standards.

Curriculum specialists have expertise in this area that can help you accomplish your planning goals. Room to Discover provides curriculum services that support school-wide planning, as well as online coaching to support individual teachers. In a few short sessions, you’ll be confident in creating custom unit plans and pacing guides, designed specifically for you and your students.

Take advantage of our free services to stay up-to-date on the latest teaching strategies and innovations. Sign-up for our free newsletter, or join the discussion on our Facebook group, the Reflective Teachers Community.

Jeff Lisciandrello is the founder of Room to Discover and an education consultant specializing in student-centered learning. His 3-Bridges Design for Learning helps schools explore innovative practices within traditional settings. He enjoys helping educators embrace inquiry-based and personalized approaches to instruction. You can connect with him via Twitter @EdTechJeff

Jeff Lisciandrello is the founder of Room to Discover and an education consultant specializing in student-centered learning. His 3-Bridges Design for Learning helps schools explore innovative practices within traditional settings. He enjoys helping educators embrace inquiry-based and personalized approaches to instruction. You can connect with him via Twitter @EdTechJeff

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

Does the Danielson Rubric improve teaching? Maybe it’s an unfair question. After all, it’s a rubric, not a training program. But…

Effective curriculum plans are built by engaging teachers in a collaborative, school-based process. Getting a head start before summer break is key.